September 20, 1915

St. John the Baptist Parish, Louisiana

“There’s a white man outside.”

“There’s a white man outside.”

The announcement slipped from Marie Claudette’s mouth before she could catch it. Josephine looked up from the book she was reading, a sharp frown forming at the corners of her mouth. She rose from the rocking chair quickly, meeting her sister at the drafty window.

And there he was, sure enough.

The man paced in front of a ragged wagon, the kind built to haul hay and hogs, its shape slouched with age. He was dirty, shirt stained and sleeve torn at the seam. He had on a floppy hat, not like a farmer, but the kind folks wear to go out dancing and drinking. It appeared that the man was in what he’d call his good clothes. And it was clear he’d been interrupted from a night of good timin’.

Darkness crept in from behind the dilapidated wagon, low-hanging clouds swallowed the last bits of moonlight, one by one. Shadows seemed to close in around him, but he didn’t notice. He muttered to himself, pacing a shallow trench into the dirt, his head swiveling between the wagon and the house. Josephine and Marie Claudette watched in silence, each wondering the same thing:

What was a white man doing out here, at this time of night?

Marie Claudette looked back at their mother. Was she expecting him? Announcing visitors was nothing new for the Brown family. Folks came and went like shadows, tired eyes and tight lips that barely met their gaze. Their porch was a wrap-around waiting room with blue bottles dancing over hopeful patients, protecting what was held sacred inside.

There were no trained doctors in their small community of Freiner. No traiteurs within about twenty miles. No one to work the roots. Now, there was a white woman who called herself a midwife ‘cross the bayou. She delivered babies and peddled high-priced medicine to respectable folks—folks who wouldn’t fraternize with the likes of the slovenly man outside. But those same people, the ones too bright and white to step foot on Brown land, sent their Black workers to get tinctures and remedies for the things white magic could not fix.

The Brown girls were used to sharing their mother, to being last on her long list of folks to care for. But it was nighttime. No one with sense would come out to the bayou at this time—not on Brown land. There were too many stories about what went on there under a full moon. They’d heard the whispers, too—laughed them off. Their mother had said folks’ fear of what they were was protection enough. But here it was nighttime, way past visiting hours, and someone had come anyway.

Someone who wasn’t afraid.

At least not yet.

But if anything about tonight was out of the ordinary, their mother didn’t show it.

She hummed as she placed stones, seeds, and pieces of bone in a wooden cup, shook it up, then spilled the contents on her altar. She stared at the debris spread out on the scuffed oak, studying each object like it spelled out some message. She let out a loud sigh.

It was the third time she’d sighed today.

“Mama?” Josephine squeaked. She was nearly a woman at seventeen, but her voice sounded like a girl just weaned from her dollies. She was tall and skinny like a string bean and wore her long, thick hair in one braid that swung down her back. Josephine, the youngest, was soft and innocent where Marie Claudette, just three years older, had inherited her mother’s strength and strong will.

And her sight, too.

Marie Claudette saw that the man carried a heavy load. It was evident in the way his steps dragged over the red dust. But there was something else. She felt his rage and distrust. She felt his raw hatred.

She saw the dark spirit hovering over his shoulder.

She moved in closer, nose to glass, to get a good look at his face, but the darkness kept it hidden. She crossed her thick arms over her stomach, hugging herself and the growing life inside her. Marie Claudette was the spitting image of her mother— fair-skinned, light green eyes, even graying early like her. But unlike her mother, she hadn’t taken to working the roots. She earned her living by reading cards, carefully shaping destinies and offering soft lies in times where the truth was too sharp to share.

Marie Claudette knew the cost of keeping secrets.

Their mother hacked into a handkerchief and placed it in the pocket of her too big britches. She was already a petite woman but lately she’d been losing weight. She’d rubbed herself with a sticky balm every morning, took honey straight from a beehive, and even rubbed her feet with anointed oil. Still, she shrank. Whatever herbs, mixtures, or offerings she’d used many times before were of no use now.

“Jul-yaa! Jul-yaaaa Brown!” the white man called out loud enough to wake the dead. He reared back and threw his head toward the moon like he was aching to let out a thunderous howl. “Jul-ya! I know you see me out here. Come on out. We need you!” His words slurred and his head rolled like a man possessed. Josephine looked on in horror, fearing the worst.

Marie Claudette balled her fists.

Julia moved slowly now, her eyebrows furled in a way that meant she knew this man. She put her debris back in the cup and set it way back on the altar. She rubbed her hands together like she was wiping dirt from her fingers and mumbled a few words. And then, when she finished her ritual, she turned her attention to the noise outside. Julia slid to the door, a look of annoyance spread across her forehead.

Marie Claudette moved to get the rifle from beside the door, but her mother shook her head. “Ain’t no need for that just yet,” Julia warned. Marie Claudette was a good shot but shooting a drunk white man, even if he was on their property, was no good for a Black woman.

Julia opened the door wide and stepped outside. She pulled the door just a little, leaving just a sliver of opening behind her. On either side, blue bottles clanked against each other offering an eerie lullaby in sync with the wind. She looked left and right, taking note of the weather and surveying the land—looking past the misshapen moss trees and straight to the sunken land near the old bayou. She zeroed in on the area, ensuring that nothing had been defiled. Julia had to make sure that this man hadn’t uncovered things meant to stay buried. When she finally looked at the disheveled man, her eyebrows raised in contempt.

“What you want here tonight, T-Boy?”

The man stomped his foot and puffed out his chest. “Don’t you call me that. Don’t you never call me that again! My name is Thomas Beauchamp. Mr. Beauchamp to you!”

If the man wanted any reaction from Julia, she had none to give. “Alright. Mr. Beauchamp. Gone and tell me what ya here for.”

The man—Mr. Beauchamp—took a few steps forward, inching closer to the porch steps. But his foot couldn’t land on the first step. It kept sliding off, like the worn wood was too slippery to grip.

Like the steps didn’t want him there.

Julia smiled at the sight. Her blue bottles set off a litany of chimes like little church bells. Finally, Mr. Beauchamp gave up. He took his big hat off, revealing a mess of red hair that hadn’t seen water in days. He nervously looked around before pointing to his wagon.

“Bernadette’s in there. She’s having pains, but it ain’t time yet. She weak and can’t keep nothing down. She ain’t talking much either. Like she ain’t got enough life in her. We not gon’ make it cross the bayou—not in her condition. I need…I need your help here.”

At this, a raw, wet wail clawed its way out of the wagon. The noise twisted through the air, drifting into the dark like a newly freed wraith. The sound startled Josephine and she stepped back from the window.

Marie Claudette eased to the door and cracked it open wider, wanting to get a better look at Mr. Beauchamp. She saw his face now, a contorted mask of pain and hatred. He had patches of gray hair on his face and bruised hollow cheeks. She could see he wasn’t nothing but a man down on his luck—he wasn’t going to harm them. But there was something else. This man, this visit would change something for worse.

“Mama,” she whispered. “Something not right with them. Don’t let ‘em in.” Julia nodded to acknowledge her daughter’s words, but she knew that she couldn’t tell Mr. Beauchamp no.

“Bring her to the steps, we’ll bring her in. She gone have to lay on a pallet on the floor though. Don’t look like she’ll make it to the back room.”

“Lay my wife on the floor like some colored woman?” Mr. Beauchamp scoffed. “Ain’t no way I can allow that.” He looked back at the wagon, wringing his floppy hat in his hands. Bernadette Beauchamp screamed louder.

“That’s all I can offer you. Your wife getting worse by the minute. My girls’ll make a pallet for her.” Julia cocked her head to the side, waiting for Mr. Beauchamp’s feet to start moving. But he just stayed there, pride anchoring his feet to the ground. “We wastin’ time,” she added. “You want all them little girls to have no mama?”

Julia knew a lot about the Beauchamps. She knew how T-Boy liked to get drunk on weekends and come home and knock Bernadette around. She knew he had a temper just like his daddy, and a knack for philandering just the same. She knew that Bernadette had married for money, only to find out too late that T-Boy’s inheritance was little more than a last name. She also knew that those four little girls, blonde-haired stair steppers, didn’t look a thing like T-Boy but were the spittin’ image of Mr. Trosclair from the market.

Bernadette let out another moan, this time followed by a loud shriek, like something ancient clawing through her throat.

“Take me in!” she yelled. “Take me in, Tom!”

Mr. Beauchamp looked from the wagon to the porch and back up at Julia. His eyes were clouded with hate, embarrassment even, but he had no choice. Julia nodded her head, encouraging him to save his wife.

He jogged clumsily to the wagon and scooped up his frail woman. She was shivering, auburn hair sticking to her neck and back. The loose blue nightgown she wore was discolored by age and soaked through with a dark, oily stain in the front. Marie Claudette and her mother exchanged knowing looks.

The porch step creaked as Mr. Beauchamp put his right foot softly on the worn boards, testing to make sure it would hold his weight this time.

“Come on. The steps not gon’ bother you again,” Julia said. The command seemed to float in the air and give warning to the blue bottles. They immediately stopped clanking.

Josephine had already set up the pallet and placed pillows around the blankets. She’d cleared away the rocking chairs to make room by the hearth. Mr. Beauchamp dragged Bernadette through the doors and lowered her onto the pallet. Josephine and Marie Claudette began placing things near their mother’s reach: A basin filled with boiled water, hog lard, a knife, thread, ergot plant, and a small container of blue paste. Julia brought a bowl of herbs from her altar and set them down by her stool. Mr. Beauchamp stepped back, lurking in the cool part of the house while the women went to work.

Bernadette was in more pain now, her moans fused into helpless screams and cries for mercy. She thrashed against the blankets, pushing herself away from the thing that was tearing through her body. Blood seeped into the thick blankets underneath her, folding into the fabric like spilled ink on paper. The fabric drank the blood in silence, inch by inch, with quiet persistence.

Bernadette jerked up, like a puppet being pulled by its invisible master. “Take it out. Please, Jesus, take it out!”

Marie Claudette forced her back down. Josephine patted her shoulders and offered words of encouragement. Still, the wailing and twisting dragged on. They’d witnessed hard births before, babies ripping through the birth canal, too eager to enter this cold world. But this, watching Bernadette’s skin shift from alabaster to dark blue, would stay with them. The memory would twist into myth, a warning that would spread across the parish.

Another horror born at Brown land.

Julia forced a tincture of dark liquid down Bernadette’s throat, clamping her hand over her mouth to keep it down. With her thumb, she smeared a thick pasty substance across Bernadette’s lips. Within minutes she was still.

Too still.

Her face slackened. Her eyes rolled back. Her tongue lolled out the left side of her mouth, like something dead.

Josephine put her hand on Bernadette’s stomach, pushing and prodding the baby to turn. Marie Claudette looked at the woman in front of them, a half dead white woman with a surely dead baby inside. And just as Marie Claudette began to conjure the right words to let Mr. Beauchamp know that his wife and baby would not see morning, a tiny baby boy slid out onto the wet quilt, feet first.

“It’s a boy,” Josephine announced to no one in particular; her eyes filled to the brim with tears. There was no joy in her voice, only deep sorrow. But Mr. Beauchamp didn’t notice. He jumped up and threw his hat into the air and caught it.

“A boy! Got damn! Four girls and finally a junior!” He proclaimed, ignorant to the eerie silence that filled the home.

Julia quickly picked the baby up and tickled his feet. But there was no sound. She turned him over and ran her forefinger up and down his back.

Still nothing.

Marie Claudette brought over the basin and the two submerged the baby in the sterile water. The water splashed wildly as they tried to baptize the baby back to life. Mr. Beauchamp stopped his celebrating, suddenly aware that the air had shifted. An unsettling sense of wrongness washed over him.

“What you doin’—what you doing to my boy?” Mr. Beauchamp demanded. “I say, what you witches doing to my boy! Stop it!”

But the women kept working, using the water to wash away the sins of the father. And as the water cleansed the baby, it was then that Josephine truly saw the tiny creature. The baby’s skin was all wrong—a purplish splotchy color that looked like someone had dipped him in ink. His spine was crooked and poking out of his back. His head was too big for his fragile body and his mouth looked like it was put on the wrong side up.

The baby boy took a sharp breath just as Mr. Beauchamp reached out to snatch him from the women. He saw the purple skin and crooked spine. He saw the twisted mouth and screamed.

He nearly threw the baby at Josephine, like the tiny ball of human flesh had scorched his palms.

“You…you did something to my boy! This thing ain’t human!” he yelled as he backed up to the front door. His mind raced between rage and fear—what had those Black witches done to his baby? What would they do to him? “What you do to him? Why?” he sputtered.

No one answered him.

The baby boy gasped for air, quick breaths that promised to be over soon. Mr. Beauchamp rushed over and pulled at his wife’s arms. “Wake up, Bernadette! Shit. Berny?” he pleaded. He looked around at the solemn faces as fear pulsed through his veins. He snatched up his wife and backed to the door. A trail of something like sliced meat fell from her body.

“No—not yet!” Julia yelled. “The balm hasn’t worn off. She’ll—”

“You stay away from me—all you. You damn hoodoo witches! I knew it. I knew I shouldn’t have come here. You just a devil woman, just like your ma!” He spat at Julia.

Josephine and Marie Claudette looked at each other, confused by Mr. Beauchamp’s allegation. His familiarity. They watched Julia closely, a cold, uneasy awareness settling over them like fog.

These two had history.

Josephine glanced at her mother and sister, afraid of how close they were to dangerous territory—a dead white family on their land. But Julia knew just how much was at stake. She knew that Beauchamp poison all too well. She had faced off with him before, many times throughout her life. She squared up, her petite body raising a bit taller in the moment. Her sparkling green eyes bore directly into his—as if they were looking into the same reflection.

Julia was tired of mincing words. “You brought her here half dead. You knew she wasn’t fit to carry another baby. Now, this baby won’t live past night, and if you take Bernadette right now, she won’t come back from it. Let me finish. Then ya’ll can be on your way. I can help Bernadette, but I’m sorry ‘bout your boy. Nothing could be done.”

Mr. Beauchamp’s eyes flickered with rage. Sparks of vengeance leaped from his glare. “Hell no! You worthless witch. I’m taking my wife. You can keep that thing you cursed. You won’t get away with it—turning my boy into that…monster! I’m gonna kill you!”

At the threat to her mother, Marie Claudette edged toward the rifle. Across the room, Josephine clutched the now dead baby to her chest, paralyzed with fear.

But Julia just smiled.

“The grave you plan for me gon’ be your own, T-frere.”

Brother.

The sisters didn’t have to look too hard to see the resemblance: same thin lips and hallow cheeks. And those eyes. Those light green eyes. The half-siblings glared at each other, each harboring the resentment of their mothers. Each smothered under the weight of their father’s transgressions.

“Devil! You always were—you and your witch ma turned my daddy ‘gainst me! Conjured him! He left you all this good land and gave me the scraps. I knew I shouldn’t have come here. I’m gone get the whole town over here. We gon have us a good hanging. And when you’re dead, I’m gonna spit on your damn grave!”

The sound of the cocked rifle split through the tension in the room. “Mr. Beauchamp, I’m gon’ ask you kindly to get out our house. Now. And I ain’t gon’ ask again,” Marie Claudette warned. Her right hand held the rifle steady and her left fingers grasped the trigger tightly.

Mr. Beauchamp’s bug eyes widened, not because of fear, but because a Black woman dared to raise a gun at him. He eased back, out of the door and turned around to stumble over the steps. Bernadette lay limp in his arms, flopping around as he huffed back to the wagon.

Marie Claudette and Julia walked out onto the porch as Mr. Beauchamp prepared his wagon.

“You bring folks on my land, T-frere, and it will be the last thing you do,” Julia warned. But Mr. Beauchamp wouldn’t let well enough alone. He was too proud to realize that a Black woman’s warning should be taken as a promise.

“You threatening me? You wait. You’ll be dead and we all gon’ be dancin’ on this land. My land! Count ya days Jul-ya.”

Julia cracked a smile then released a haughty laugh from some place buried deep within. “You can kill me, but you’ll never have Brown land. When I die, I’m going to take this whole town with me.”

Mr. Beauchamp shook his head, the liquor waning and the rage shining through. He hawked a thick wad of spit onto the ground—it nearly landed on the porch step. He snapped the reigns and commanded the horses to get on.

The three women watched as the wagon sped away into the night. Josephine came up next to her mother, a tiny swathed capsule cradled in her arms. “Mama, what we gon’ do with this baby boy,” she asked.

Julia sniffed and let out a fit of hacking coughs. She took her handkerchief out again and spit into it before burying it back into her pocket. Marie Claudette looked at her, but Julia refused to meet her eyes. They both knew the cost of keeping secrets.

The blue bottles began to sing again, a grim chorus rising as moonlight creeped over Brown land. Julia joined in, humming a melody that weaved itself into the strange sound.

The wind picked up. Leaves stretched from gnarled branches, swaying in an uneasy rhythm. Marie Claudette inhaled the metallic odor floating in the air.

A jagged flash of lightning ripped across the sky casting a strange ray of light beyond the trees. For just a few seconds, the darkness peeled back, revealing the sacred place:

A sea of shallow graves, each with a small offering—wilted flowers, bones, dolls. The light show stopped, and with it the cover of night swallowed their secrets once more.

“We do what we’ve always done. Feed the land.”

Stay tuned for the Part 2 of this episode on May 29.

The storm is coming. Take cover.

Special note:

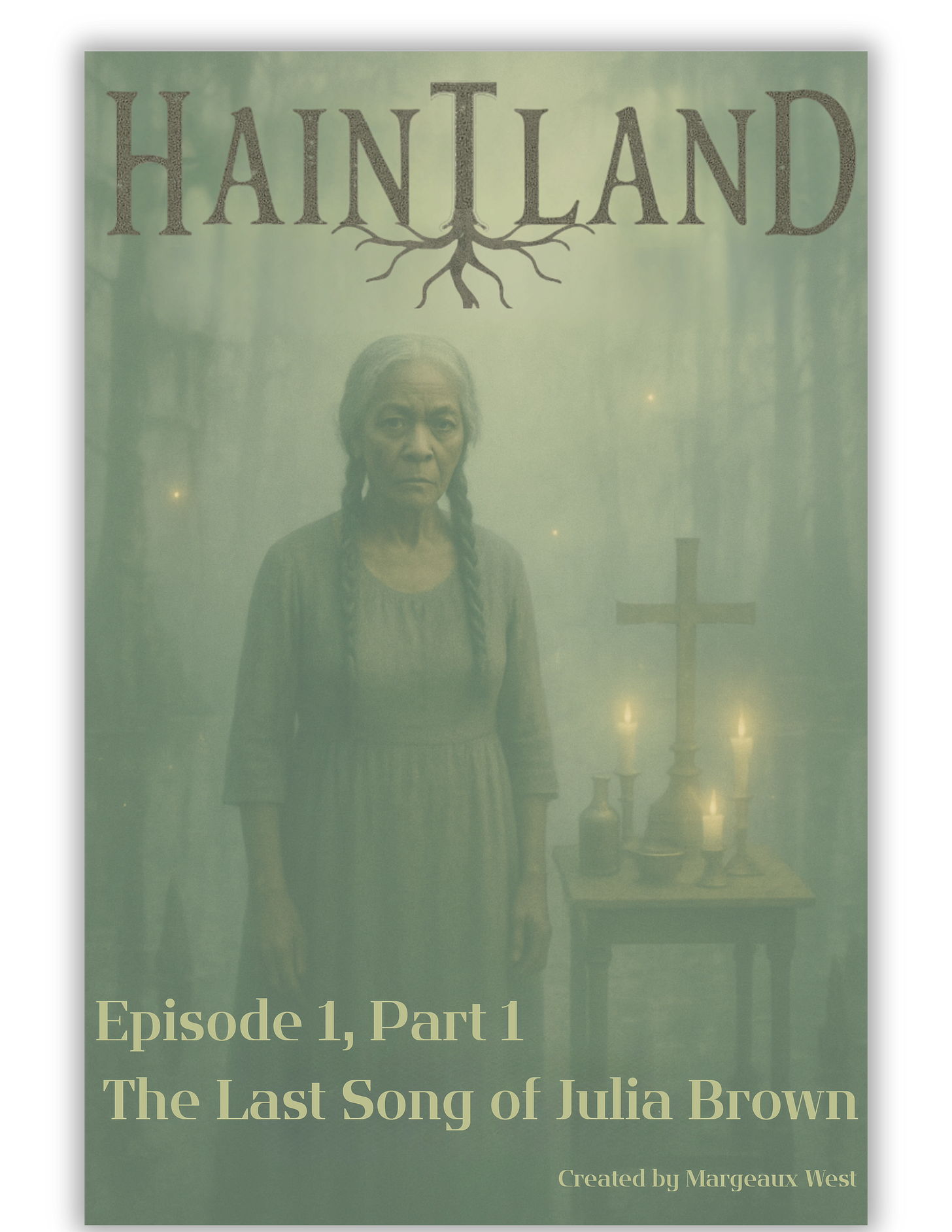

The images created for this episode were rendered using a combination of graphic design tools and generative programs. If you enjoyed this story, please like and share. Your support helps me get closer to my goal of hiring talented artists to create even richer images.

Captivating!!!

THIS is how you open a story! LOVED every bit of it! ✊🏿